The library raised me. It was warm, steady, safe. It did not move every year, did not forget me at recess, did not ask why I wasn’t in dance class or horseback riding lessons like the other girls. It did not laugh when I tried to belong. It did not belong, either. It was quiet and vast, a place where being alone was not a punishment but a possibility.

Between kindergarten and senior year, I attended seven different schools. My dad was absent, and my mother was largely hands-off—stretched thin by bills, exhaustion, and the ever-growing realization that she shouldn’t have had children. There was no PTA involvement, no structured extracurriculars, no careful curation of childhood experiences. When I scored in the 99th percentile on some standardized test in third grade, I wasn’t sent to the gifted and talented program because we didn’t have a car, and the school hosting it was across town. I watched from the edges as other girls giggled and whispered about their dance classes, riding lessons, their soccer team victories, their sleepovers in houses much larger than whatever tiny apartment we lived in at the time. At recess, I was ignored or teased for my too-big or too-small hand-me-down clothes, the classmate who tried too hard or not enough.

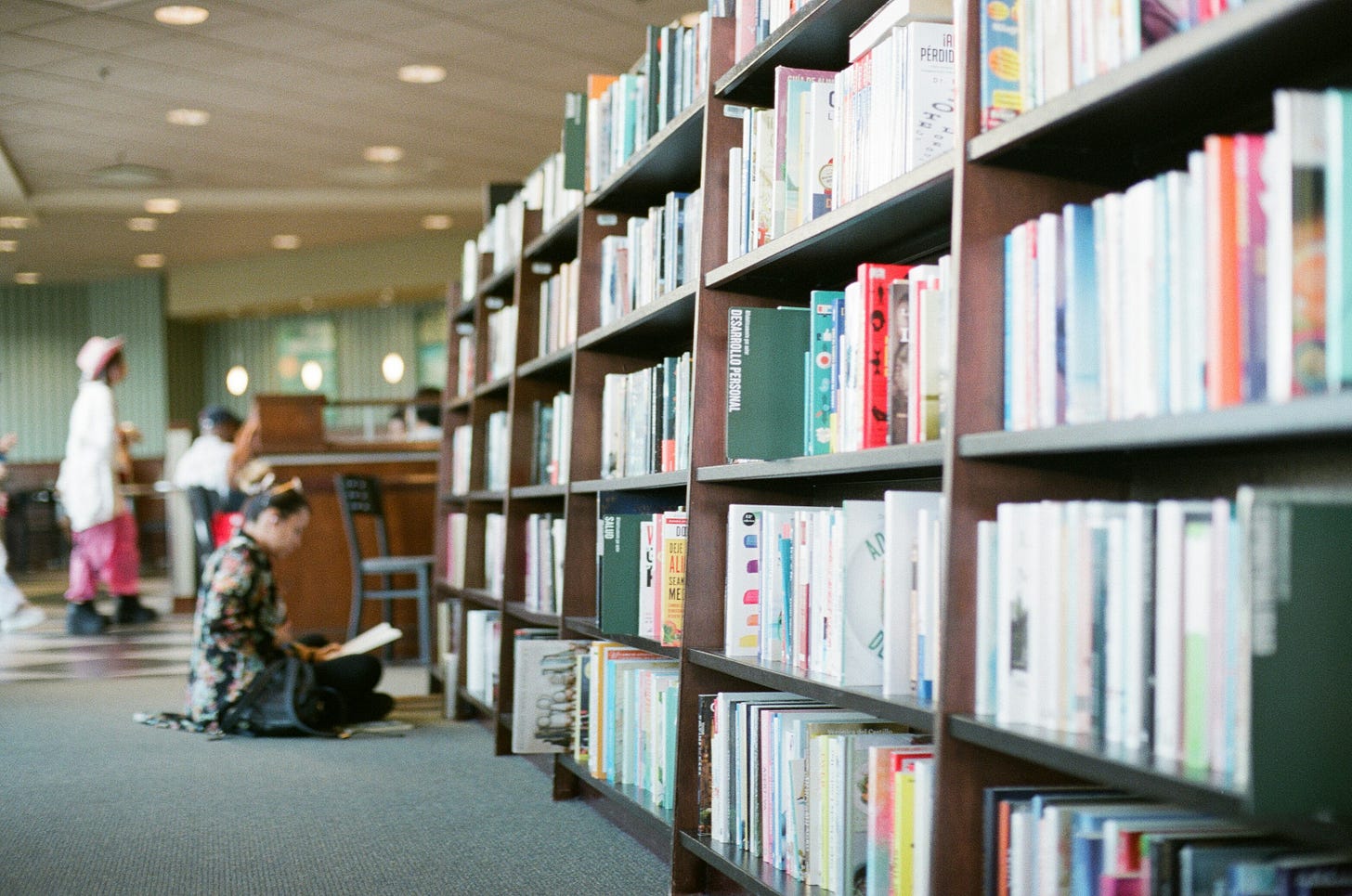

But the library never turned me away. It had no auditions, no fees, no dress code. It did not ask if I could afford to be there. It was the first place that offered me a kind of belonging, not by making me fit in, but by making fitting in unnecessary. There were no cliques in the stacks, no social hierarchies at the long wooden tables where I spread my books out like a lifeline. The library whispered that I could be something more than a girl left out on the playground. It handed me stories about other people’s lives, other people’s loneliness, other people’s ways of making it through.

Now, Iowa lawmakers want to take that away. House File 274 strips public libraries of their protections, allows books to be labeled obscene, makes the people who safeguard them into criminals. They say they are protecting children. From what? From books that tell them they are not alone? From stories that remind them the world is bigger than their hometowns, their families, their own small, struggling lives?

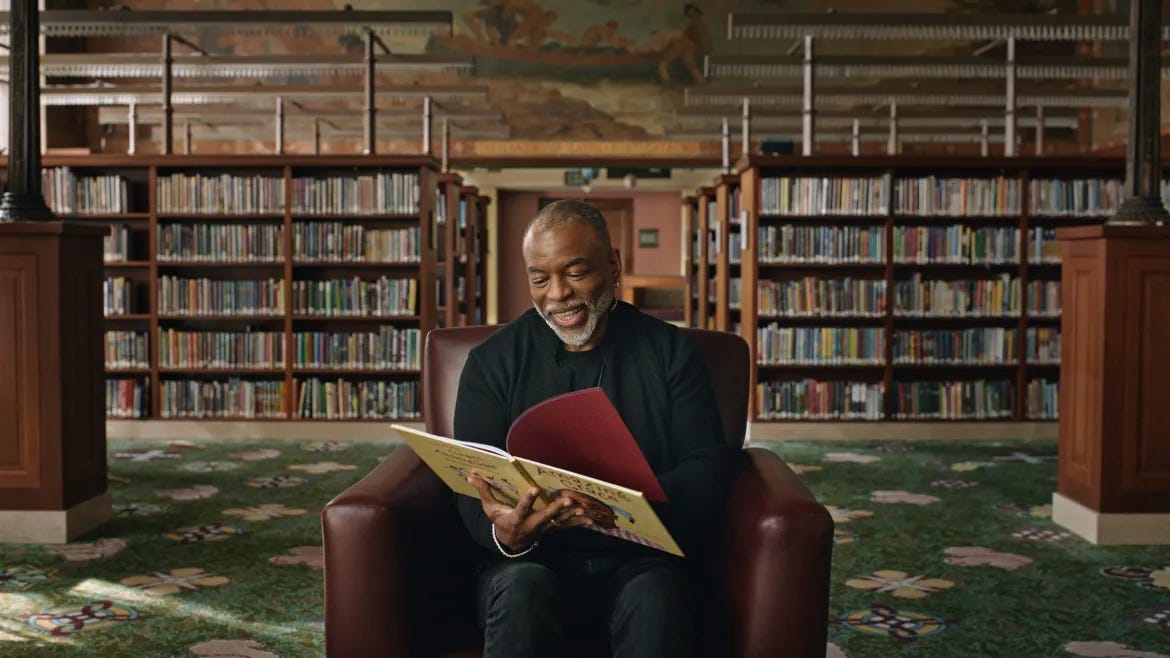

I was a child once, one who needed the library more than they will ever understand. The people behind these laws do not know what it means to stand between the shelves on a lonely afternoon and feel, for the first time, that the world is reaching back. They do not understand what it is to be a kid with nowhere else to go, a kid who learns about friendship from the Baby-Sitters Club, about justice from To Kill a Mockingbird, about survival from Hatchet. They do not know what it means to find pieces of yourself in books when the real world offers you no such mirrors.

What they are really protecting is ignorance, the comfort of small, safe narratives. They want to make the world smaller, to strip it of complication, to pretend that banning a book erases the truth inside it. They are not saving children; they are keeping them from saving themselves. They are taking away the stories that might have shown them another way, that might have handed them a map out of whatever loneliness, whatever smallness, whatever desperation they have yet to name.

The library never promised me an easy world. It only promised I would not have to face it unarmed. It trusted me to choose, to read, to learn. That was the deal. That was the gift. And now, they want to take it away.